G.P.A doesn't spell J.O.B

While many college students stress over maintaining high GPAs to stand out in the job market, career advisers say higher GPAs don’t necessarily mean better chances. Some employers don’t use GPAs at all in determining employment potential, even for top-level jobs.

Despite grade inflation, students continue to struggle to achieve high grades. Getting a better job, improving their chances of being accepted into graduate school and social pressures are among the reasons.

The No. 1 reason behind pursuing higher education is to get a “good job or career,” cited by 58% of respondents in a Gallup survey. “Learning and knowledge” was a distant second with 23%.

Ulyssia Dennnis

Assistant Directory of Employer Engagement at Engineering Career Services at University of Illinois

Still, most employers use GPA only a baseline in considering candidates, according to Jennifer Neef, associate director of the Career Center at the University of Illinois.

“I have never had an employer say, ‘I need someone with a 4.0 GPA,’” Neef said.

A GPA of 3.0 is the typical baseline for most companies, according to Ulyssia Dennis, assistant director of employer engagement at Engineering Career Services at the University.

This remains true even for some top companies. Laszlo Bock, then senior vice president of people operations at Google, said in a New York Times article in 2013 that GPAs were “worthless as a criteria for hiring”. As a consequence, Google no longer requires a transcript or GPA during its hiring process.

Jennifer Neef

Associate Director of The Career Center at University of Illinois

Jason Boys

Associate Director of Career and Student Services at the School of Labor and Employment Relations at University of Illinois

“We found that they don’t predict anything,” Bock said.

Kevin Pitts, Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education at the University, said grades are relevant but less than people think. “I’ve never in my career ever had anyone asked me what my GPA was,” Pitts said. “As a professional, I’m judged on my performance,” he added.

With the U.S. unemployment rate at 3.8%, lowest since the late 1960s, GPA restrictions are fewer because there is more demand than recent graduates, Neff said.

Jason Boys, associate director of career and student services at the School of Labor and Employment Relations at the University, agreed, adding that applications for graduate programs also are decreasing as the economy has improved.

“People don’t apply to grad school; they work,” Boys said.

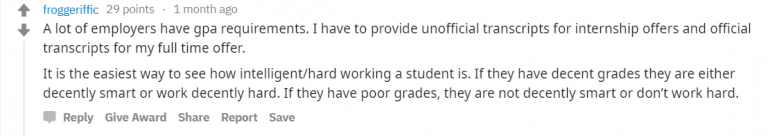

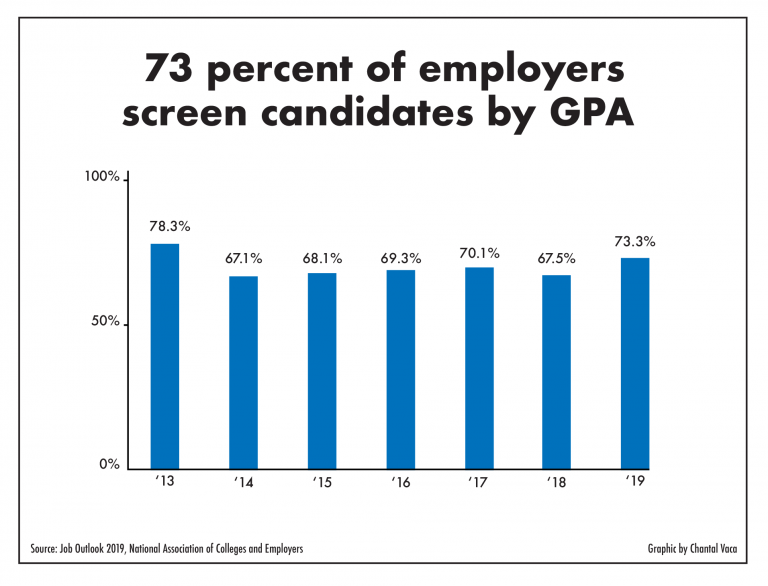

Still, according to a 2019 report by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, GPA remains an important screening criteria for some employers. According to the report, 73.3% of employers surveyed — the highest since 2013 — said they used GPA to screen candidates.

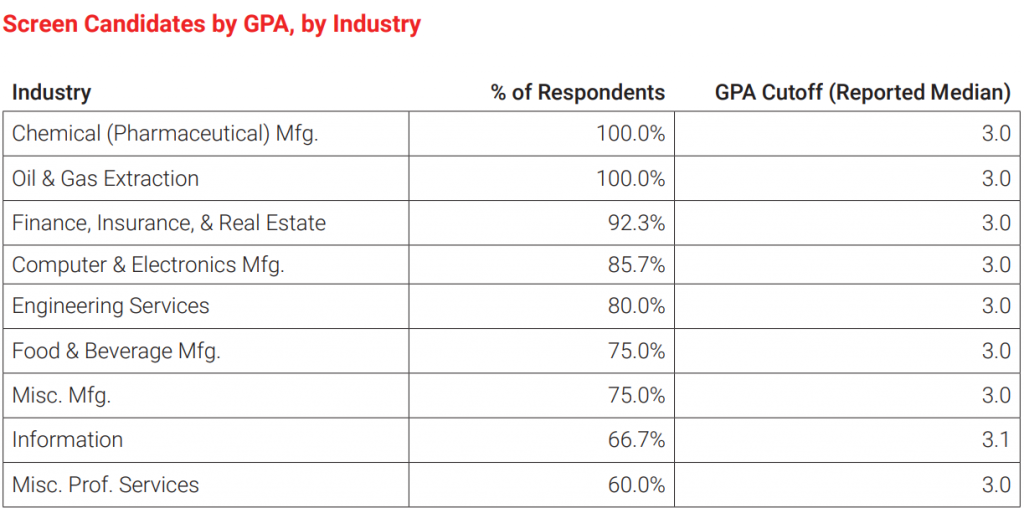

Among the industries that use GPA to screen candidates, most were in chemical manufacturing, oil and gas extraction, and finance, insurance and real estate. Among nine types of industries surveyed, eight used 3.0 as their GPA cutoff. The “information” industry was the only one where the cutoff was 3.1.

The average GPA generated by University of Illinois courses is 3.38, meaning even below-average students would have no problem meeting most GPA cutoffs.

In an interview with CNBC, executive resume writer Laura Smith-Proulx said that GPAs above 3.5 showed high achievement but that the achievement level was applicable in the first years after a student graduated. Other experts agreed the importance of GPAs fall significantly after a couple of years of being in the job market.

The worthiness of GPAs also has loud contrarians. In “What Straight-A Students Get Wrong,” an opinion piece in the New York Times, organizational psychologist Adam Grant said: “Getting straight A’s requires conformity.” He argued that perfect transcripts were a consequence of taking easier classes that didn’t get students out of their comfort zone.

In spite of some experts’ relative disregard of use of high GPAs as a hiring criterion, recent graduates have to include it in their resumes, according to Nell Madigan, associate dean of the School of Labor and Employment Relations at the University, “or a company will assume that it’s terrible.”

Nell Madigan

Associate Dean of the School of Labor and Employment Relations at the University of Illinois

Is a degree worth it?

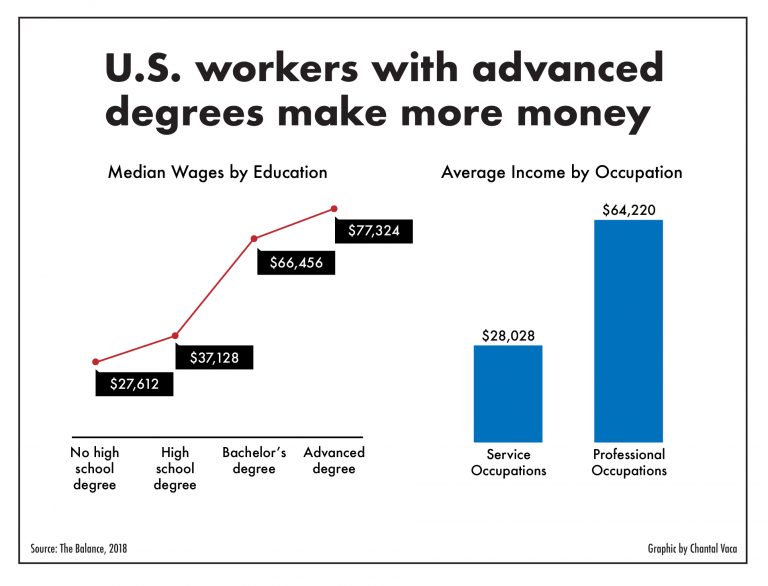

According to a report by the career specialized website The Balance Careers, the average salary for employees, both new and experienced, with a bachelor’s degree is $66,456, almost 50% more than the $44,564 median income in the United States.

University of Illinois undergraduates who obtained full-time employment after graduation received an average of $60,885 a year, according to the 2017-18 Illini Success Report. This amount puts the University in 100th place nationally, according to the website Payscale.com.

The National Association of Colleges and Employers survey revealed 100% of respondents planned to hire graduates with a bachelor’s degree from the class of 2019. Bachelor’s degrees are the most demanded, with 83.1% of all the new hires having a bachelor’s and 10.6% having a Master’s.

While demand favors bachelor’s graduates, U.S. workers with advanced degrees made, on average, 16% more money.

Online courses

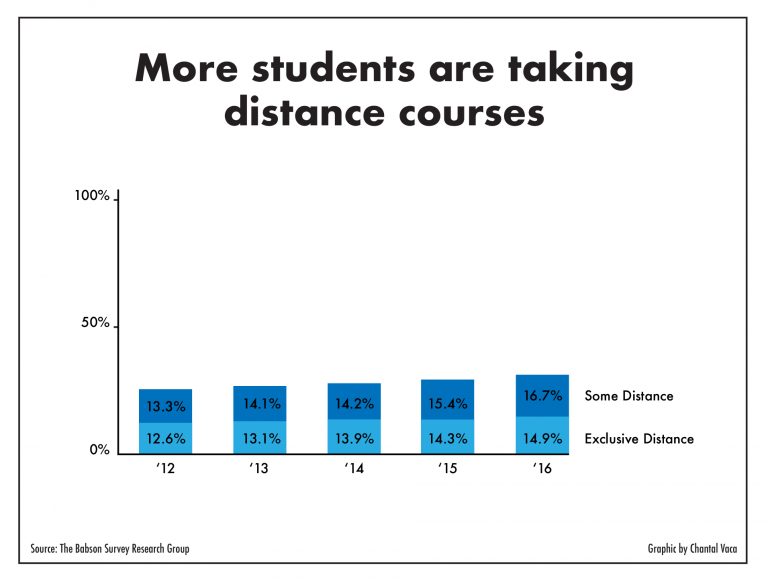

By fall 2016, the number of students taking at least one distance education course reached 6,359,121, representing 31.6% of all postsecondary students in the U.S. A little less than half were enrolled exclusively in distance courses. More were taking a combination of distance and non-distance courses.

The number of on-campus students nationwide decreased by 6.4% between 2012 and 2016, according to a 2018 report, “Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States,” by Babson Survey Research Group.

According to the Illinois Distance Education Enrollment Report, the state’s colleges and universities reported a total of 303,808 enrollments in online and blended courses during the fall 2018, a 5% increase compared with fall 2017. Blended courses are classes that integrate face-to-face and online learning.

The University accounted for 33,499, a little more than 10%, of all online enrollments, making it the public university with the largest online course enrollment, second only to the online enrollment of independent for-profit DeVry University, where 65,017 students were enrolled.

Some remain hesitant about online educational quality and online degree graduates.

A literature review published in 2009 explored employers’ perceptions of online degrees. The paper listed concerns such as “lack of rigor, lack of face-to-face interactions, increased potential for academic dishonesty, association with diploma mills,and concerns about online students’ true commitment.”

These concerns are influenced by other factors, such as name recognition of the degree-granting institution, appropriate level and type of accreditation, and candidates’ relevant work experiences. The study concluded there still might be “a marked stigma attached to online degrees throughout the hiring process.”

More recent research, however, indicates the stigma may be gone. A 2018 report by Northeastern University’s Center for the Future of Higher Education & Talent Strategy concludes most human resources leaders no longer view online degrees as inferior to their traditional counterparts. The survey included 750 human resources leaders at U.S. employers among all industry sectors and organizational sizes.

Of the respondents, 61% believed credentials earned online were of equal quality to their in-person counterparts. This is a significant increase from the 40% who believed so in 2013. While 39% of respondents still viewed credentials earned online as being of lower quality, the trend seems to show an improving perception.

As for the University’s online degrees, the official transcripts don’t state whether a degree was earned online or on campus. It’s up to each graduate to disclose, or not disclose, whether his or her degree was earned online.

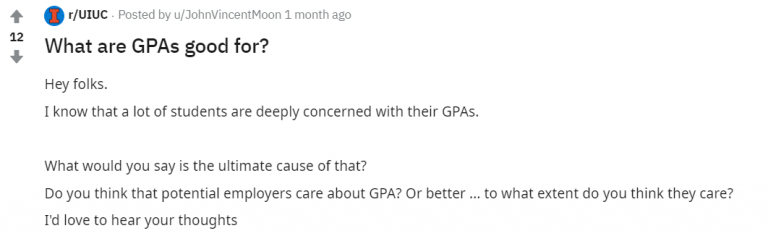

Why do students care about GPAs?